Today’s post comes from Laurel Gray, a processing intern with the Textual Division at the National Archives in Washington, DC. It’s the first in a series on the archival ramifications of the Watergate scandal.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Watergate. Many are familiar with the scandal that resulted in President Richard Nixon resigning from office, but today we’re exploring some of the lesser known stories surrounding the event.

Before we get into it, it’s important to know a bit about Richard Nixon. Throughout his decades-long political career, Nixon worked obsessively on controlling his public image. Watergate destroyed all that work in an instant, and by August 1974 many people saw Nixon as a crook and a criminal, which is not how he wanted to be remembered.

Nixon came up with a simple solution to his problem by looking to the future. His Presidency is one of the most well documented in history. Nixon wanted to keep this treasure trove of archival materials for himself and hide the worst things from the public. If he could control his Presidential materials, then he could shape his historical legacy the way he wanted. For Nixon, privacy was protection, and after Watergate he fought hard for that protection.

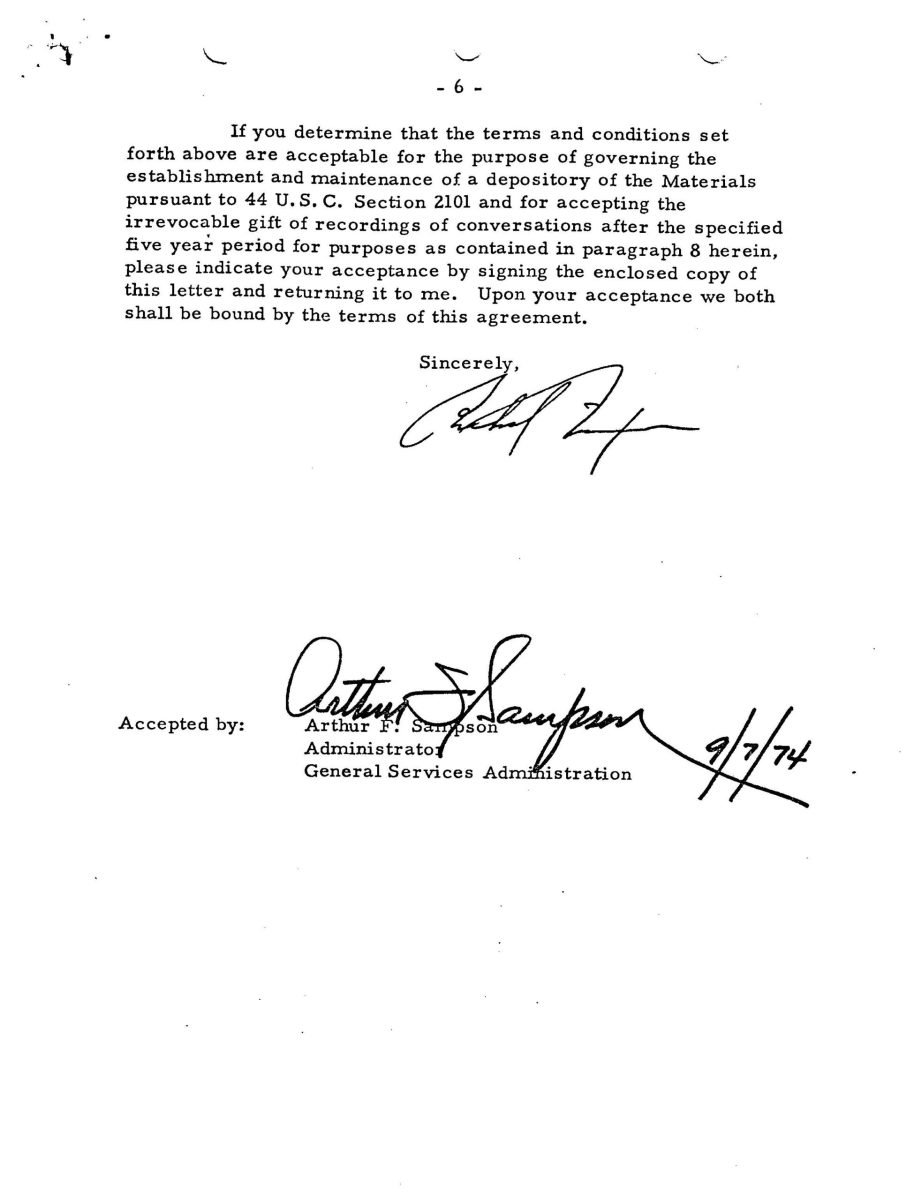

The full story of Nixon’s fight for the ownership of his Presidential materials spans decades and involves lawsuits, Presidential Libraries, the Supreme Court, broken deals, legislation … the list goes on. Today we’re looking at the beginning of the archival story with the signing of the Nixon-Sampson Agreement in September 1974.

What was the Nixon-Sampson Agreement?

The Nixon-Sampson Agreement came about during pardon discussions between Ford and Nixon staffers. The agreement guaranteed that Nixon would have ownership of his Presidential materials after he left office. This included any documents, photographs, and, yes, taped conversations that he or his staff created during his Presidency.

What made the agreement so controversial is that it also stated that Nixon could destroy these taped conversations after 10 years or in the event of his death, whichever came first. As Senator Gaylord Nelson—who opposed the Nixon-Sampson Agreement—pointed out, “If Mr. Nixon died tomorrow, those tapes … are to be destroyed immediately.”

The agreement sparked outrage in Congress and across the historical and archival communities. So how did Nixon get away with it in the first place?

Nixon exploited loopholes to create the Nixon-Sampson Agreement. First, he didn’t work with the Archivist of the United States, James B. Rhoads. Instead, Nixon worked with Arthur F. Sampson, the Administrator of the General Services Administration (GSA). At the time, the GSA oversaw the National Archives, and therefore Nixon didn’t have to consult Rhoads as long as he had the help of Sampson.

Nixon’s other advantage? He had 200 years of history on his side.

Before the creation of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, every President of the United States, beginning with George Washington, took his Presidential papers with him after leaving office. Presidents passed down their papers to family members, donated them, discarded them, you name it. Even though this method wasn’t ideal for archival preservation, it was tradition.

In fact, in preparation for his pardon, President Ford requested an opinion from the Attorney General on what to do with Nixon’s materials. Attorney General William Saxbe reluctantly sided with Nixon, citing the sanctity of this tradition. With history and bureaucracy on his side, Nixon was able to do the impossible in the attempt to repair his image in the wake of Watergate.

In the month that followed Nixon’s resignation, several major events had taken place that helped the disgraced President take more control over his historical legacy. On September 6, the Attorney General submitted an opinion hesitantly supporting Nixon’s claim to ownership of his Presidential materials. The next day, Nixon signed the Nixon-Sampson Agreement, securing that claim to ownership. The day after that, President Ford pardoned Nixon of his crimes in connection to Watergate.

In just three days, Nixon was absolved of his crimes and had control over most of the evidence that would say otherwise. The Attorney General’s opinion, Ford’s pardon, and, most importantly, the Nixon-Sampson Agreement essentially gave Nixon permission to rewrite history.

But as we’ll see in this series, the story doesn’t end there. Nixon’s success was short-lived as Congress passed legislation to nullify the Nixon-Sampson Agreement. Nixon, of course, fought back, but it was a long and challenging process that lasted for decades.