Off the coast of Indonesia’s easternmost island, on a bright January day this year, Nesha Ichida waded into the crystal-clear waters of a secluded lagoon, gently cradling a 15-week-old zebra shark named Charlie. She lowered her hands into the water and Charlie swam free — weaving his long, striped tail fin as he disappeared into the reef.

A short time later, Ichida, a local marine biologist, released two more shark pups into the water.

“We had been working toward that moment for three years, we were so proud,” she recalled recently. “My hope is that Charlie and the others will be ambassadors for their species — and all the other sharks we want to protect.”

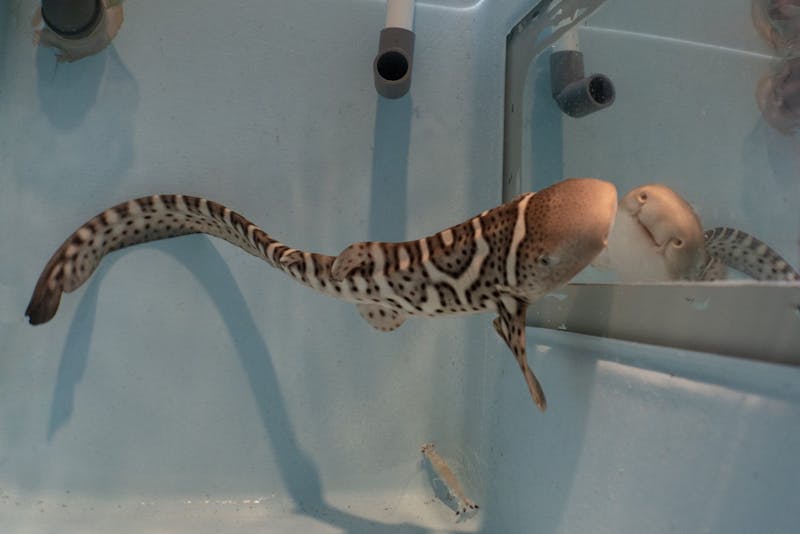

Charlie nine weeks after hatching.

The three pups (Charlie and his sisters Kathlyn and Audrey) are the first endangered sharks ever to be bred in captivity for the purpose of being released into the wild. Laid in a Sydney aquarium, their fragile egg casings were carefully secured and boxed up for the 8,000-kilometer (5,000-mile) journey — by land, air and sea — to the protected waters of Raja Ampat, a remote archipelago known for its extraordinary biodiversity.

The pups are pioneers in a global effort known as ReShark, a multinational partnership of nearly 80 aquariums, universities and environmental organizations — including Conservation International and its local partner Konservasi Indonesia — that has launched a captive breeding program to reintroduce threatened sharks into the wild.

It’s an audacious plan. For decades, captive breeding programs have successfully reinvigorated struggling populations of orangutans, California condors and other wildlife. But the approach had never been tried with marine species.

“Witnessing those first zebra sharks swim away was simply electrifying,” said Mark Erdmann, who leads Conservation International’s Asia-Pacific marine programs and came up with the idea for the program. “I’ve had this dream since 2015, and to have it finally realized after years of false starts, trials and tribulations, and hard work is truly awesome.”

Erdmann figured that if sharks could be released from aquariums back into the wild to somewhere they wouldn’t be caught, they just might be able to come back from the edge of extinction.

“Sharks are some of the most misunderstood, and threatened, species on the planet,” Erdmann said. “We have an opportunity to give them a fighting chance.”

A rare haven

In just about any place in Southeast Asia, there’s a good chance Charlie and the other pups could have been caught and killed for their fins after being released. But Raja Ampat is different.

Nearly two decades ago, this ecosystem was almost destroyed by unregulated commercial fishing, poaching and damaging practices such as dynamite fishing. But conservation efforts — led by local communities — gradually changed all that. Today, this remarkable archipelago in Southwest Papua, Indonesia, is made up of nine interconnected marine protected areas covering about 67,000 square kilometers (26,000 square miles) that are home to the greatest diversity of marine life on the planet.

Fish populations have rebounded; sharks, whales and rays have returned; poaching is down 90 percent and coral reefs are recovering. At the same time, ecotourism has flourished — while local people’s access to education, food and livelihoods have improved. Raja Ampat is a monument to effective marine conservation — the perfect place for ReShark to test the idea that captive breeding and release could boost shark populations.

View of the zebra shark release site in Wayag lagoon, Raja Ampat.

A long journey home

Charlie, Kathlyn and Audrey’s story began in a tank at the Sea Life Sydney Aquarium, where they were bred from zebra sharks that had been captured off the coast of Australia — one of the few places where the species is thriving, thanks to a ban on shark finning.

Kathlyn newly hatched from her egg casing.

Zebra sharks were once as common in Raja Ampat’s sandy seabeds as in Australia. But overfishing, driven by demand for their fins, caused the species to all but vanish in the wild. Zebra sharks became endangered and by 2020, the Raja Ampat population had dwindled to roughly 20 individuals.

Yet as zebra shark populations shrank in the wild, they were thriving in public aquariums.

“We had this fascinating conservation asymmetry playing out,” Erdmann said. “In the wild, these animals are really in trouble, but in captivity they are breeding like rabbits.”

Though the breeding program held tremendous promise, the team was in uncharted waters, said scientist Iqbal Herwata, who works with Konservasi Indonesia, one of the project partners.

“Aquariums were so successful at breeding zebra sharks that many had to separate the males from the females because they couldn’t handle the number of eggs being laid,” Herwata said.

For many aquariums, this was too much of a good thing. It prompted many of them to place a moratorium on breeding for more than a decade.

At the same time, breeding zebra sharks wasn’t as straightforward as putting the males and females back in the same tanks — the genetics had to line up.

“Introducing genetic variants that are not well-suited to the local environment can hinder population recovery and disrupt ecosystems,” Herwata said. “In other words, the breeding zebra sharks had to belong to the specific population that had originally inhabited Indonesian waters.”

Laura Simmons of the Sea Life Sydney Aquarium packs up an egg casing.

Back at Sea Life Sydney Aquarium, a suitable breeding pair began mating and producing eggs. The plan was on.

At roughly three months old, and still in their egg casings, Charlie and six other shark embryos were placed in individual plastic bags with about a gallon of oxygenated seawater and packed into insulated Styrofoam boxes for the journey to their new home in Indonesia.

Keeping the eggs, and later the hatchlings, in a comfortable, oxygen-rich environment proved challenging. Partway through that first trip from Sydney to Raja Ampat, the shipment of eggs got stuck in customs at Jakarta’s airport on a Friday due to a clerical error. The eggs were transferred to a local aquarium for the weekend while the issue was sorted out. Unfortunately, it was too late for two of the embryos, which died, likely due to a lack of oxygen.

“It was a lesson learned,” Erdmann said. “Now we ship the eggs on a Monday.”

Hatchery in Raja Ampat.

Once in Raja Ampat after their long journey, the remaining three eggs (two were found to be infertile) went to hatcheries specially built for them at partnering dive resorts. For nearly two months before the eggs hatched, young local scientists known as “shark nannies,” who were trained to care for the pups, monitored the tanks’ water quality and kept the eggs clean. Once hatched, the pups had to eat up to seven times a day. The nannies charted their growth — feeding them live snails, clams, shrimp and crabs so they could learn to fend for themselves.

Shark nanny feeding a zebra shark pup.

“They grow about two and a half times as fast in our hatcheries as they do in aquariums,” Herwata said. “Once they reach roughly 50 centimeters (20 inches) in length, we move them into fenced sea pens where they can swim among seagrasses and live corals and begin searching for wild prey — but we can still monitor them and make sure they aren’t eaten by anything.”

When Charlie and his sisters reached roughly a meter (about 3 feet) in length, it was time to head into the wild. Researchers tagged them for future monitoring; placed each one in a large, covered tank; and loaded them onto a boat headed for the Wayag lagoon, nearly 130 kilometers (80 miles) away.

‘The sky’s the limit’

With three zebra shark pups hatched, raised and released into the wild in Raja Ampat, the team has proof of concept. Egg casings continue to arrive at the hatcheries and are being prepared for release. Over the next decade, ReShark plans to release at least 500 zebra shark pups into the Raja Ampat archipelago. The team has already begun to explore new locations and is building hatcheries that will function well for other endangered shark species, and even rays.

In Indonesia, the project could reach beyond Raja Ampat, as the Indonesian government hopes to replicate its success in other locations, and with other species of sharks, said Fahmi, a senior scientist with the Indonesian National Innovation and Research Agency, and an adviser to the ReShark initiative. Like many Indonesians, he uses just one name.

The project has implications for ecosystems all over the planet. Worldwide, nearly 400 species of sharks are threatened — from the mighty great white to the docile walking shark. Shark populations have dropped dramatically in the past 50 years due mainly to the shark fin trade.

The project also has the potential to build empathy for these misunderstood animals, which have helped maintain a delicate balance in the world’s ocean ecosystems for 450 million years.

“To me, the sky’s the limit for this world-leading initiative,” Erdmann said. “It’s immensely satisfying, knowing we played a role in bringing them back where they belong. I’m confident that in a few years’ time, visitors to Raja Ampat will be able to enjoy seeing zebra sharks throughout the region.”

View of the hatcheries at sunset, Raja Ampat.

Mary Kate McCoy is a staff writer at Conservation International. Want to read more stories like this? Sign up for email updates. Also, please consider supporting our critical work.