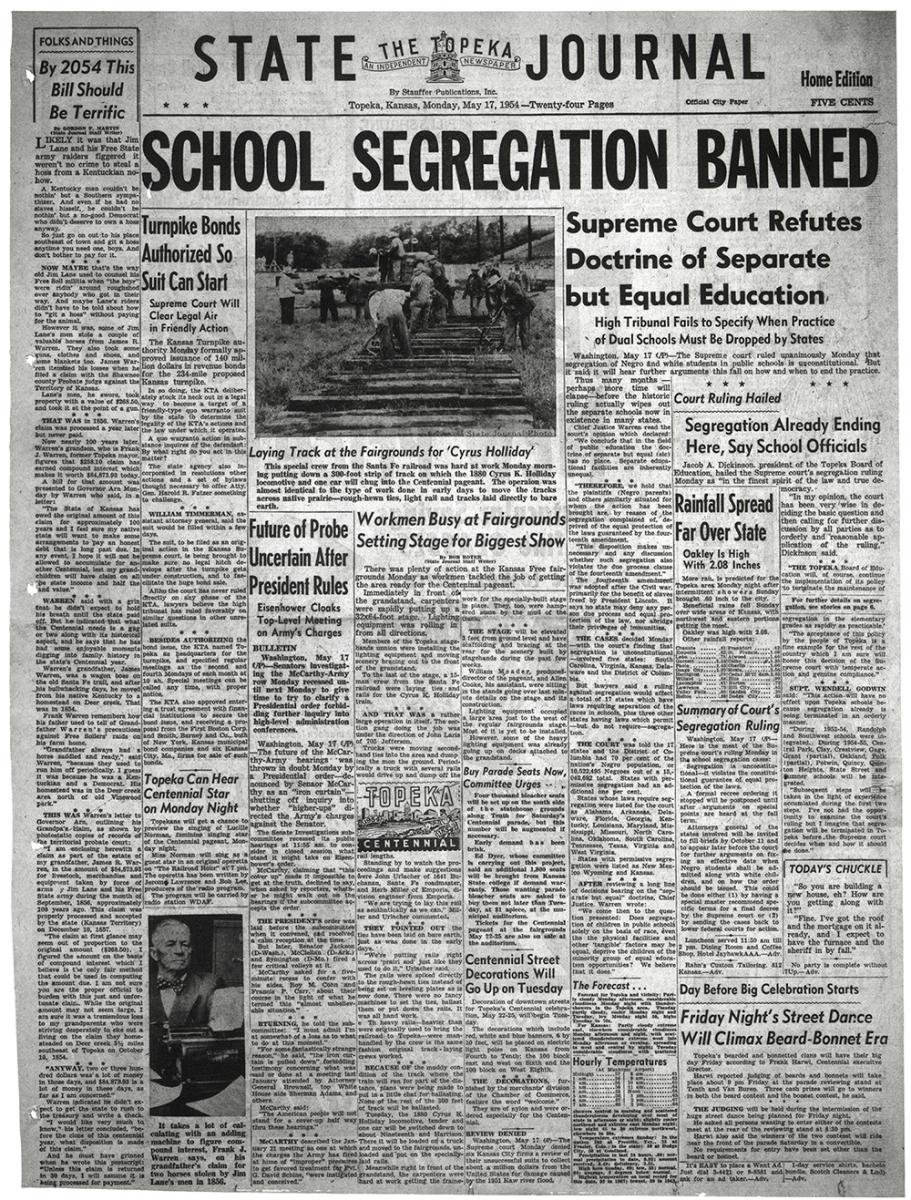

70 years ago the Supreme Court issued its Brown v. the Board of Education ruling. Today’s post has been adapted from a piece by Daniel Holt, who served as the Director of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum in Abilene from 1990 to 2008 and was a member of the Brown v. Board 50th Anniversary Commemoration Commission in 2004. Holt passed away in 2023.

What do the following have in common? Laws preventing discrimination based on age, sex, disability, or religion; the Americans with Disabilities Act; Title IX; affirmative action; and the rectification of a major foreign policy dilemma when the United States, at least on paper, finally moved to assure the world that it was indeed a country where “all men are created equal.”

If you answered Brown v. Board of Education, you are correct.

While most Americans know the Brown case ruled that segregated schools were inherently unequal, the legacy of the case goes far beyond that, for it provided the basis for assuring equal treatment in many other venues and in our personal lives.

There are many myths about Brown, and the history of how the case reached the Supreme Court is very long and complicated. As early as 1950, the New York office of the NAACP, under the leadership of Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall, was working in several states to strike down the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson ruling that “separate but equal” school facilities were constitutional.

When five cases reached the Supreme Court from Delaware, South Carolina, Virginia, Kansas, and the District of Columbia, they were combined by the Court into one case: Oliver L. Brown et. al. v. The Board of Education of Topeka (KS) et. al. Overall, there were about 200 plaintiffs.

In the Topeka case alone, 13 parents were plaintiffs representing 20 children. There are many who believe that the reason for using the Brown name was that he was the only male plaintiff in the Topeka case. It was, after all, the 1950s.

All cases reached the Court on appeals after having failed to overturn Plessy. Arguments began in December 1952. The Court asked the plaintiffs to reargue the case to address issues beyond equal facilities. Those arguments began in December 1953.

Two of the cases had major differences from the others. A dissenting opinion in the South Carolina Briggs case stated that segregation was “inequality,” and in Topeka, the judges added a statement to the decision that segregation was detrimental to Black children.

Topeka was also different in that the separate school facilities for Black and White children were similar, raising the issue that segregation of itself was harmful to the children, regardless of access to “equal” facilities. Topeka’s high schools were integrated in the classroom but not in social or athletic programs. The elementary schools were, by state law, segregated in towns with populations greater than 15,000.

The primary question, oversimplified, concerned the intent of Congress when the 14th Amendment was passed in 1868 and what constituted equal protection under that law.

On May 17, 1954, Chief Justice Earl Warren answered that question, writing for the Court: “Does segregation of children in the public schools solely on the basis of race, even though the physical facilities and other ‘tangible’ factors may be equal, deprive the minority group of equal educational opportunities? We believe it does.”

It was a unanimous decision.

The commemoration of the 50th anniversary of Brown began in 1988, when Cheryl Brown Henderson, daughter of plaintiff Rev. Oliver Brown, who represented her sister, Linda, was asked by a friend what was being done to commemorate the decision. “Not much,” she replied.

Spurred on by this question, Brown Henderson organized the Brown Foundation for Educational Equality, Excellence and Research. When one of the segregated elementary schools in Topeka became available for purchase in 1990, she and other supporters approached the Kansas congressional delegation to encourage the National Park Service to consider making Monroe School a national park.

On October 26, 2003, President George W Bush signed legislation establishing the school as a National Historic Site, which was dedicated on May 17, 2004. Today, the school is part of the larger Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Park.

The Brown Foundation also sought national recognition for the commemoration, and on September 18, 2001, Congress passed and the President signed the law establishing the Brown v. Board of Education 50th Anniversary Commission, operated through the U.S. Department of Education, to “plan and coordinate educational activities . . . and to encourage, plan, develop and coordinate observances.”

The National Archives quickly realized that because NARA holds the federal records pertaining to the five cases that constitute the Brown case and other federal civil rights cases, we should take a leadership role in making those sources available through our website and programs.

NARA commemorated the anniversary through a variety of initiatives to help educate the public about the decision and its consequences through the use of our holdings. In addition to a special exhibit of the Brown decision, the National Archives held a number of free public programs at our nationwide facilities including book talks, educational workshops, and films. National Archives staff also created a number of related resources, including a Reference Information Paper and a cover article in Prologue magazine.

As we commemorate Brown’s 70th anniversary, you can learn more about its legacy through the holdings and resources at the National Archives:

In celebration of the landmark Supreme Court decision that altered the landscape of education in the United States, the National Archives is presenting “The Legacy of Brown v. Board of Education, 70 Years Later” on Thursday, May 16, at 7 p.m. ET/4 p.m. PT.